- Home

- Red Death(Lit)

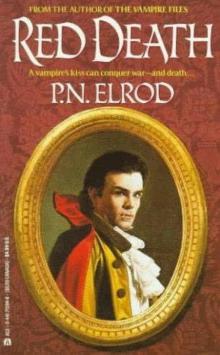

P N Elrod - Barrett 1 - Red Death

P N Elrod - Barrett 1 - Red Death Read online

P N Elrod - Barrett 1 - Red Death

Long Island, April 1773

"You are a prideful, willful, ungrateful wretch!"

This was my mother speaking-or rather screeching-to me, her only son.

To be fair, it was not one of her better days, but then she had so few of those that none of us were accustomed to noting any difference in her temper. Good or bad, it was best to treat her with the caution and deference that she demanded, if not openly, then by implication. Today, or at least at this moment, I had failed to observe that unspoken rule of behavior, and for the next five minutes was treated to a sneering, acid-filled lecture detailing the negative aspects of my character. Considering that until recently she'd spent fifteen of my seventeen years removed from my company, she had a surprisingly large store of knowledge to draw upon for her invective.

By the time she'd paused for air I'd flushed red from head to foot and sweat tickled and stung under my arms and along my flanks. 1 was breathing hard as well from the effort required to hold in my own hot emotions.

"And don't you dare glower at your mother like that, Jonathan Fonteyn," she ordered.

What, then, am I to do? I snarled back to her in my mind. And she'd used my middle name, which I hated, which was why she'd used it. It was her maiden name and yet one more tie to her. With a massive effort, I swallowed and tried to compose my face to more neutral lines. It helped to look down.

"I am sorry, Mother. Please forgive me." The words were patently forced and wooden, fooling no one. A show of submission was required at this point, if only to prevent her from launching into another tirade.

Unhampered by the obligation of filial respect, the woman was free to glare at me for as long as she pleased. She had it down to a fine art. She also made no acknowledgment of what I'd just said, meaning that she had not accepted my apology. Such gracious gestures of forgiveness were reserved only for those times when a third party was present as a witness to her loving patience with a wayward son. We were alone in Father's library now; not even a servant was within earshot of her honey-on-broken-glass voice.

I continued to study the floor until she moved herself to speak again.

"I will hear no more of your nonsense, Jonathan. There's many another young man who would gladly trade places with you."

Find one, I thought, and I would just as cheerfully cut a bargain with him on this very spot.

"The arrangements have been made and cannot be unmade. You've no reason to find complaint with any of it."

True, I had to admit to myself. The opportunity was fabulous, something I would have eagerly jumped for had it been presented to me in any other manner, preferably as one adult to another. What was so objectionable was having everything arranged without my knowledge and sprung on me without warning and with no room for discussion.

I took a deep breath in the hope that it would steady me and tried to push the anger away. The breath had to be let out slowly and silently, lest she interpret it as some sort of impertinence.

Finally raising my eyes, I said, "I am quite overwhelmed, Mother. But this is rather unexpected."

"I hardly think so," she replied. "Your father and I had long ago determined that you would go into law."

Liar. I had decided that in the years she had been living away from us in Philadelphia. If only she had stayed there.

"It is our fondest hope that you not only follow in his footsteps, but surpass him in your success."

My mouth clamped tight at the unmistakable sarcasm in her emphasis of certain words. This time the anger was on Father's

behalf, not for myself. How could she think him a failure?

"To do that, you must have the best education possible. Don't think that this is a mere whim of ours. I-we have studied the choices carefully over the years and determined that Harvard is simply not capable of delivering to you the best that is available...."

Just after breakfast, she'd sent for me to come see her in the library. I was mildly apprehensive, wondering what the trouble was this time. It was yet too early in the day for me to have done anything to offend her, unless she'd found something to criticize in the way I chewed my food. I was not discounting it as a possibility.

We'd eaten in uncomfortable silence, Mother at her long-empty spot at one end, and my sister, Elizabeth, across from me as usual in the middle. Father's place at the head of the table was empty, as he was away on business.

Such silence at the morning meal was new to this household. It had settled upon us like some heavy scavenger bird with Mother's return home. Elizabeth and I had learned that it was better to remain quiet indefinitely than to speak before spoken to lest we draw some disapproving remark from her.

The servants were not as lucky. Today one of the girls chanced to drop a spoon, and though no harm was done, she received a lengthy rebuke for her clumsiness that left her in tears. Elizabeth exchanged glances with me while Mother's attention was distracted from us. It was going to be a bad day for everyone, then.

Somehow we got through one more meal under this threatening cloud. Weeks earlier, my sister and I had agreed to always finish eating and leave at the same time so that neither had to face such adversity alone. We did so again, asking permission to be excused and getting it, and had just made good our escape when one of the servants caught up to us and delivered the summons. I was to come to the library in five minutes.

"Why couldn't she have said something when we'd been right there in the room with her?" I whispered to Elizabeth after the servant was gone. "Is speaking to me directly so difficult?"

"It's her way of doing things, Jonathan," she replied, but not in a manner to indicate any approval. "Just agree with whatever she says and we'll sort it out with Father later."

"Do you know what she wants?"

"Heavens, it could be anything. You know how she is."

"Unfortunately, yes. May I come see you afterward? I shall need you to bind up my wounds."

She burst into that radiant smile reserved only for me. "Yes, little brother. I'll go look for some bandages immediately."

Mother had seated herself in the chair next to Father's desk; it would have been overdoing things to actually take over Ms chair. She was canny enough to avoid that. The idea was lo suggest his invisible presence approving her every action and word. I was sharply aware of this and not at all fooled, but not about to inform her of it. In the month since her return, I'd had to face her here alone on a dozen minor offenses; this was starting out no more differently than the others. I'd guessed that she'd noticed the new buckles on my shoes and was about to deliver a scorching opinion of their style and cost. The other lectures had been on a similar level of importance. I was glad to know that Elizabeth was standing by ready to soothe my burns when it was over.

Mother had assumed the demeanor of royalty granting an anxiously awaited audience, studying some letter or other as I walked in, her wide skirts carefully arranged, the tilt of her head just right. She could not have been an actress, though, for she was much too obvious in her method and would have been hooted from the stage in a serious drama. Farce, perhaps. Yes, she might have been perfect at farce, playing the role of the domineering dowager.

Marie Fonteyn Barrett had been very beautiful once, slender, graceful, with eyes as blue as an autumn sky, her skin milk white and milk soft. So she appeared in her portrait above the library fireplace. In the twenty years since it had been painted the milk had curdled, the grace turned to stiff arrogance. The eyes were the same color, but had gone hard, so that they seemed less real than the ones in the painting. Her hair was different as well. No more were the flowing black curls of a young bride; now it was piled high over her creased

brow and thickly powdered. In the last month it had grown out a bit and needed rearranging. Perhaps she would even wash it out and begin afresh. I could but hope for it. Her constant stabbings and jabbings at that awful pile of lard and flour with her ivory scratching stick got on my nerves.

The curtains were open and cold April sunshine, still too immature for warmth, seeped through the windows. The wood in the fireplace had not been lighted, so the room was chilly. Mother was a great believer in conserving household supplies unless it concerned her own comfort. The lack of fire gave me hope that our interview would be mercifully short.

"Jonathan," she said, putting aside the paper in her hand. I recognized it as part of the normal litter on Father's desk, something she'd merely grabbed up to use as a prop. Why was the woman so artificial?

"Mother." The word was still awkward for me to say.

She smiled with a benevolent satisfaction that raised my apprehensions somewhat. "Your father and I have some wonderful news for you."

If the news was so wonderful, why was Father not here to deliver it with her? "Indeed, Mother? Then I am anxious to hear it."

"You will be very pleased to learn that you will be going up to Cambridge for your university education."

That was hardly news to me, but I put on something resembling good cheer for her sake. "Yes, I am very pleased. I have been looking forward to it all year."

Her brows lowered and eyes narrowed with irritation. Perhaps I was not as pleased as had been expected.

"I shall do my absolute best at Harvard to make you and Father proud of me," I added hopefully.

Now her mouth thinned. "You will be going to Cambridge, Jonathan."

"Yes, Mother, I know. Harvard University is located in Cambridge."

Somehow, I had said the wrong thing. Fury, red-faced and frightening to look upon, suddenly distorted her features so she hardly seemed human. I almost stepped backward. Almost. Her rages were not uncommon. We'd all seen this side of her many times and learned by trial and error how to avoid them, but this one mystified me. What had I done? Why was she-?

"You dare to mock me, Jonathan? You dare?"

I raised one hand in a calming gesture. "No, Mother, never."

"You dare?" Her voice rose enough to break my ears, enough to reach the servants' hall. Hopefully, they would know better than to come investigate the din.

"No, Mother. I swear to you, I am not mocking you. I sincerely apologize that I have given offense." Such words came easily; she'd given me ample opportunity for practice over the weeks. I finished off with a bow to emphasize my complete sincerity. Yet another opportunity to study the floor.

Thank God that this time it worked. Straightening, I saw her color slowly return to normal and the lines in her face abruptly smooth out. This swift recovery was more disturbing to me than her instant rage. Since her return, I'd quickly adjusted to the fact that she was not at all like other people, but that was hardly a solace during those times when her differences were so acutely demonstrated.

Dominance established, she resumed where she'd left off, almost as though nothing had happened. "You are going to Cambridge, Jonathan. Cambridge in England, Jonathan," she repeated, putting a razor edge on each syllable as though to underscore my abysmal ignorance.

It took me some moments to understand, to sort out the mistake. I suppose that she'd been anticipating a torrent of enthusiasm from me. Instead, my face fell and from my lips popped the first words that came to mind. "But I want to go to Harvard."

That's when the explosion truly came and she started calling me names.

You know the rest.

What was she saying now? Something about the virtues of Cambridge. I did not interrupt; it would have been pointless. She wasn't interested in my opinions or plans I might have made. Any and all objections had been drowned in the hot tidal wave of her temper. To resurrect them again would only aggravate her more. As Elizabeth had reminded me, I could sort it all out with Father later.

Did Father know about this? I couldn't believe that he would not have spoken to me about it before leaving yesterday. Surely he would have said something, for he, too, had planned that I should go to Harvard. That she had carefully waited until he was absent before breaking her news took on a fresh and ominous meaning, but I couldn't quite see the reason behind it yet. It was difficult to think while she talked on and on, pausing only to get the occasional nodding agreement from me at appropriate times.

Why was she so concerned about my education after fifteen years of blithe neglect? Marie Fonteyn Barrett had been singularly uninterested in either of her children since we were very small. It was a mixed blessing for us, for growing up without a mother had left something of a blank spot in our lives. On the other hand, what sort of broken monsters might we have been had she stayed with Father instead of moving to Philadelphia?

She'd only made the long journey from there to our home on Long Island because of all the turmoil in that city. With the rebels stirring things up at every opportunity, it had become too dangerous to remain, so she had written Father, and he, being a good and decent man, had said her house was there for her, the doors open. Her swift arrival caused us to speculate that she had not actually waited for his reply.

She'd just as swiftly assumed the running of the household in her own manner, subtly and not so subtly disrupting every level of life and work. Surprisingly, few servants left. Most were very loyal to Father and had the understanding that this was to be only a brief visit. When things had settled back to normal in Philadelphia, Mother would soon depart from us.

A likely chance, I thought cynically. Surely she was enjoying herself too much to leave.

She paused in her speech; apparently I'd been delinquent in my latest response.

"This is... is marvelous to hear, Mother. I hardly know what to say."

"A 'thank you' would be appropriate."

Yes, of course it would. "Thank you, Mother."

She nodded, comically regal, but not a bit amusing. My stomach was starting to roil in reaction to the tempest between my ears. I had to get out of here before exploding myself.

"May I be excused, Mother?"

"Excused? I should think you'd want to hear all the rest of the details we have planned."

'Truly I do, but must confess that my brain is whirling so much now I am hardly able to breathe. I beg but a little time to recover so that I may give you my best attention later."

"Very well. I suppose you'll run off to tell Elizabeth everything."

To this, a correct assumption that was really none of her business, I made another courtly bow upon which she could apply her own interpretation.

"You are excused. But remember: no arguments and no more foolishness. Going to Cambridge is the greatest opportunity you're ever going to receive to make something of yourself."

"Yes, Mother." I bowed again, inching anxiously toward the door.

"This is, after all, for your own good," she concluded serenely

Anger flushed through me again as I turned and stalked from the room. How fond she was of that idea. God save me from all the hideous people hell-bent on doing things for my own good. So far there'd been only one in my life, my mother, and she was more than enough.

Quietly shutting the door behind me, I slipped down the hall until there was enough distance between us for noise not to matter, then began to run as though the house were on fire. Not bothering with a coat or hat, I threw myself outside into the cold April air. The woman was suffocating. I needed to be free of her and all thought of her. My feet carried me straight to the stables. With its mud, muck, and the irreverent company of the lads, this was one place I would be safe.

"Over here, Mr. Jonathan!"

My black servant, Jericho, waved at me. He was just emerging from the darkness of one of the buildings. Though he was primarily my valet and therefore supposed to keep to the house, neither of us paid much attention to such things. He was fairly high up in the household hierarchy an

d able to bend a rule here and there as long as nobody minded. If he chose to play the part of a groom, he suffered no loss in status, because working with horses was a source of pleasure for him. Right now, he was a godsend, for he had saddled up Roily, my favorite, and was leading him out to me.

I couldn't help but laugh at his foresight. "How did you guess? Magic?"

"No magic," he said, smiling at the old joke between us. He used to tease the servant girls about being able to read their deepest thoughts and being a sharp observer of human nature made him right more often than not. The younger ones were awed, the older ones amused, and one rather guilty-hearted

wench accused him of witchcraft. "I'd heard that Mrs. Barrett wanted to speak to you. Every other time you've come here to ride it off."

"And here I am once more. Thank you, Jericho. Will you come with me?"

"I rather assumed you would prefer the solitude."

P N Elrod - Barrett 1 - Red Death

P N Elrod - Barrett 1 - Red Death